The Large Apocalypses: Capturing Dystopias

War is Peace. Freedom is Slavery. Ignorance is Strength.

- George Orwell

A lesson in history

The word utopia was first coined by Thomas More in 1516. It was his book’s namesake. Etymologically, it means "no place" coming from the Greek οὐ (“not”) and τόπος (“place”). In another land and language, however, utopia is a term for a perfect world. Lacking all flaws, (moral, material, or political) - a utopian world is one where literally everywhere you see the sun gleaming, you hear everything slowed down to a mermaid-song drawl, or you feel the warmth that you get when bodies touch in the cold of December.

With that obligatory dictionary word vomit out of the way, I can talk about why I care about utopia, or why you should.

You shouldn't.

That’s all there is to it. Obsessing over an imagined perfect world leads to nothing but disappointed frowns and manic laughter from green-haired clowns who keep trying to tell you how they got the scars 'round their mouth’ for some reason. Besides what the hell even is a utopia? Everyone has their own heaven, their own peace, and their own perfect. Mine is a library, yours might be a patisserie in Paris, the wind blowing on a mountaintop, or the arms of a lover.

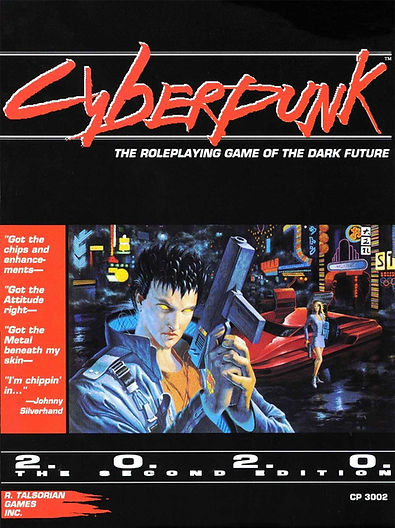

What I am more interested in, therefore, is dystopia. I'm sure all of you reading this have at some point or another read a piece of dystopian fiction. Notice how utopian fiction isn't a genre? Plots and stories need to be interesting and they need conflict, which, by definition is impossible in a utopian society. Even stories seemingly set in a perfect world usually revolve around the degeneration or the dark underside of that world, but I digress. Whether it's Orwell's infamous “Nineteen Eighty-Four” (which is definitely in support of right-wing talking points, and Orwell definitely wasn't a staunch communist,) or something more popular like the “Hunger Games”, or in other forms of media, like the “Cyberpunk 2077”, “The Game”, or the “Blade Runner” movies, dystopian fiction has existed for a long, long, long time, and I absolutely love it.

"Aryaveer, are you a masochist and a sadist who enjoys sadness and seeing people in pain? How can you love dystopia?"

Well, dear Reader, in fact, I am. Consuming dystopian literature and art is like feeling the warmth of your palm condense when you put it against the glass in icy winter - your reality is the consequence of yesterday. But more to the point, dystopian fiction is, in my feeble opinion, the greatest educator out there, because, frankly, we're living in one. Sure, we aren't quite at the point of choosing 24 kids to fight a kill-or-be-killed gladiatorial battle for glory (yet), but the systemic issues plaguing our society aren't too far enough from Katniss' home of District 12. Poverty, extreme classism, and the unequal distribution of basic human rights and resources don't sound that far off, do they?

Fons et origo: dystopia

Where does dystopian fiction come from? This question is important because looking at a work of social commentary (which dystopian fiction is), necessitates understanding the context in which it was written, and more importantly, the society on which it is commenting.

The commonly held belief is that Aldous Huxley, with his 1932 book Brave New World, kick-started the dystopian genre. What is interesting about Brave New World is that once you flip through the pages, all the predominant traits of a dystopian work are visible. The social commentary, the carefully constructed rigid social order, the outcast outside the system, and the protagonist within the system who becomes disillusioned with it and seeks change. Even more material plot elements, like a wasteland beyond the society, social degeneracy being normalized, the drug that the order uses to subjugate their subjects, all originate in Brave New World. The dynamic of Bernard and John perfectly demonstrates the ways in which the societal order changes people. Brave New World was written to be and lives on as, a cautionary tale against sacrificing individuality and human connection for the sake of technological development and social stability.

Huxley is obsessed with individuality, personal freedom, pleasure, and conformity, and the interplay between these ideas. How much are we willing to do to conform? Can you, should you, perhaps, chase pleasure at the cost of individuality? None of those questions have clear answers, perhaps they never will, but Brave New World tries to give answers, and that alone makes it an important piece of literature.

But Brave New World did not just ‘create’ dystopian fiction. It also acts as the forefather of my favorite genre of media, maybe ever: cyberpunk. And lo, we get to my favorite part of this article: getting to geek over my favorite game and talk about its important socio-political messaging.

Welcome to Night City

In Cyberpunk 2077's Night City, you can equip invisible skin, buy a flying car, and get killed by corrupt cops all in a day’s work! Keanu Reeves, aside from playing another Johnny, delivers a masterful performance as the long-dead-but-somehow-not rockerboy Johnny Silverhand, who is a staunch defender of the common Joe and a hater of all things (Amazon) Arasaka - as a pastime he loves being an arse to everyone around him. Any law-lovers please reach out and tell me if that jest will get me in trouble. Anyway, Johnny, like all of us, has healthy outlets for his anger: like nuking Arasaka Tower and dying in the process.

All ethical ramifications of the proceeding nuclear holocaust aside, the game outright tells us that it didn't matter that their headquarters literally get nuked off the face of the Earth, because by the time the game (and by extension us, the protagonist, V,) rolls around, Arasaka is again the biggest megacorp on the planet. What? A massive unregulated beast of a corporation faces no consequences for a massive crisis and bounces back to full strength immediately while the masses suffer their tyranny? Boy howdy, never seen that before! The game explores (and explodes) the idea of capitalism, profit at all costs, and what it means to be a good person in a world that basically gives you no chance to be one. There are smaller stories littered throughout cyberpunk that delve deeper into these concepts. My personal favorite: cyberpsychosis.

The idea of cyberpsychosis is that when someone installs too much chrome/cyberware/body modifications, they lose their sanity as their body struggles to keep up with their newly enhanced parts. Thus, they end up going (most of the time) on a psychopathic, unhinged, homicidal rampage devoid of any emotion except rage and often a desire for vengeance against a particular person or entity. Cyberpsychosis is interesting because it is representative of how society breaks the downtrodden. There is a debate within fans and diegetically within Night City itself too, about whether cyberpsychosis is actually a real disease, or just a mental health epidemic masquerading as a material problem. It is implied that all cyberpsychosis is, is the after-effects of prolonged agony under a hyper-capitalistic society that cares only for profits for the megacorporations, at all costs, and here that cost is the people’s sanity.

In the original Cyberpunk 2020, the tabletop role-playing game that the game is based on, the character you play has a stat called ‘Humanity’. In this interpretation of the world, when you run out of Humanity (by committing heinous acts, installing cyberware, or being scared shitless) you go cyberpsycho, and the Game Master (who represents the society you struggle under) takes control of your character. The cyberpunk genre has always been about this. It is high-tech glamor mixed with low-life squalor. Whether you look at ‘Altered Carbon’, ‘Perfect Blue’, ‘Alita: Battle Angel’, or ‘Ghost in the Shell’, the cyberpunk genre permeates the fabric of pop culture and warns us about the dangers of a capitalistic market run rampant.

The world’s French exit

And yet cyberpunk is only a small subgenre within dystopia. Another pervasive representation of dystopia is in the idea of the post-apocalypse. You've read the Hunger Games, I assume? Yeah, that. The concept of post-apocalyptic fiction is to take our world, end it, and then see what happens next. Maybe it's aliens or zombies. Maybe AI takes over the world and for some reason sends an Arnold-shaped android back in time. Or maybe America and Russia stop dilly-dallying and finally start a nuclear war.

In the Hunger Games, you don't actually know what ended the world. It is hinted that it was a combination of nuclear war, overpopulation, resource depletion, and the big daddy of apocalypse, climate change. Unfairly disregarded by many as juvenile and childish, the Hunger Games series is actually a nuanced commentary on overconsumption, systemic inequality, fascism, rebellion, Hollywood, and a cult of celebrities. The gaudy flashiness and showmanship of the Capitol bleeds through every pore of the books. The Capitol always stands over the rest of the story as a reminder of the real power controlling what happens. What unfolds always seems like a machination of the Capitol and President Snow, or at most an act of rebellion. There aren't many parts of the story or even the character's actions that don’t somewhat pertain to the Capitol, giving the impression that nothing is free from its influence. The extreme overconsumption represented by the Capitol and its people, and the inequality District 12 faces are indicative of larger issues in the society of Hunger Games.

Something else that The Hunger Games excels at is portraying the totality of the control that fascism exerts on society. The way that rebellion and revolution are framed is darkly realistic. It's not a total flipping of the social order, it's a violent replacement of one fascist figurehead with another. The imagery of an arrow flying not into Snow, but into Coin's heart, is a grounded way of showing the way that power corrupts. None who seek power can be pure of heart, as the Hunger Games tells us, and the dystopian world it is set in is deeply intrinsic to this message.

So, what now?

So, what was the point of this article? Did I just wanna gush about my favorite game, get nostalgic about the Hunger Games, and flaunt my knowledge of literature? Yes. But I also love dystopia. Every iteration of a dystopia has a meaning behind it. When Ray Bradbury was writing Fahrenheit 451 I doubt he could have guessed the long reach of his work and how it went on to become a seminal masterpiece on censorship, technology, addiction, and assimilation. The power of dystopia is to cast a Black Mirror on our world, and show us what happens when our problems are taken just a bit further ahead. It's like one of those funhouse mirrors where everything reflects back weirdly, and here you get to see all the twisted, broken pieces of the world taken apart and put back together into a slightly unfamiliar, slightly familiar amalgamation of issues.

So, go ahead, and find some dystopian stuff to watch, read, or play. Have fun, and enjoy the broken world you inhabit for the brief moments you're transported to these sweet hellholes. And if you ever feel like you want to, think about these worlds a little: What do they mean to you? What does the author wanna say to you? And what, if anything, does it tell you about your world?

Written by Aryaveer Singh